`After returning from Khojaly, I lived psychological problems` – British journalist

“İt was my duty to report that the victims of Khojaly were Azerbaijanis”

“I was 36 at the time and the only dead body I had seen close up was that of my grandmother, peacefully asleep in her coffin. It was shocking to realise that when we die, we all look like broken dolls”

“I drank to relax myself on planes but I understood that was not the long-term solution”

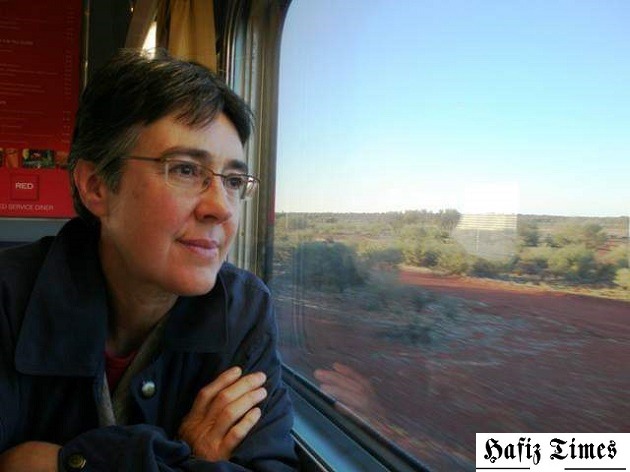

Helen Womack is one of the live witnesses of the Khojaly genocide on February 26, 1992. Helen Vomak, an employee of the famous British newspaper Independent, visited Azerbaijan in connection with the Khojaly genocide, witnessed the atrocities committed by Armenians against Azerbaijanis and made articles in the press about it. Helen Womack has been interviewed by Azerbaijani journalist Hafiz Ahmadov.

HafizTimes.com presents the exclusive interview with journalist Helen Womack.

-I am British. I worked in Moscow for 30 years, from 1985 to 2015. I reported for “Reuters”, “The Independent”, “The Times” (of London) and “the Fairfax” newspapers of Australia (“The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age of Melbourne”). I am the author of “The Ice Walk – Surviving the Soviet Break-up and the New Russia” (Melrose Books, 2013).

Now I live in Budapest. I am a writer for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), finding out how refugees from Afghanistan, the Middle East and Africa are adapting to their new lives in Europe.

-How do you remember Khojaly?

-It was a painful experience, where the truth unfolded gradually.

All wars are terrible and there are always faults on both sides. The travelling from Moscow to the war zone was not easy. And the armenians, with their large overseas diaspora, were better organised at media relations. So it may have seemed that we journalists had more sympathy for Armenia.

We heard that something dreadful had happened in Khojaly. My job was to assess whether it had been a battle, with military casualties, or a massacre of civilians.

We arrived in the middle of the night and instead of taking us to rest at a hotel, our Azerbaijanis hosts took us straight to the mosque in Agdam, where four bodies were laid out in a makeshift morgue. From a professional PR point of view, this was not a very clever move by the Azerbaijanis. For one thing, we were tired and uncomfortable. But in a way, the very primitiveness of this PR approach made me think the Azerbaijanis were telling the truth.

The next day, crowds began appearing at the mosque, searching for their relatives. Many were still missing on the mountainside.

We went to a cemetery and I saw women keening over at least 75 fresh graves. Some of them were decorated with dolls, suggesting children or young people had been buried. At the railway station, train carriages had been turned into a makeshift hospital and I interviewed doctors and wounded victims there.

It became clear to me there had indeed been a massacre of civilians. In the past, I had written with sympathy for the armenians, for example during their earthquake in 1988. But this time I knew it was my duty to report that the victims of Khojaly were Azerbaijanis. I reported what I saw and I stand by my reports. But overall, I remain neutral and balanced on the question of Nagorno-Karabakh and do not have an opinion on the situation now, as I have not followed it recently.

I saw four dead bodies in the morgue at the mosque; also crowds searching for their relatives, women weeping over at least 75 freshly dug graves in the Agdam cemetery and train carriages with wounded victims.

-How do you remember dead children, innocent people in Khojaly? What did you feel there?

-I was very affected by the sight of the dead bodies, which were horribly mutilated. I was 36 at the time and the only dead body I had seen close up was that of my grandmother, peacefully asleep in her coffin. It was shocking to realise that when we die, we all look like broken dolls.

I understood that children were among those buried in the cemetery. It was harrowing to hear the women making the ritual crying over the graves. I was also upset to hear the stories of injured people whose loved ones were missing on the mountainside. I felt numb. I did my job. I held myself together somehow but when I returned home, I unravelled.

-What changed in your own life after the horrible killings and deaths you saw with your eyes in Khojaly?

-When I returned to Moscow, I immediately fell ill with pneumonia. After that, I began having psychological problems. War correspondents are not supposed to speak about this but the trauma affects us. Seeing death close up made me think of my own death. At first, I became afraid of flying. Then I became afraid of going on the metro. I drank to relax myself on planes but I understood that was not the long-term solution. In the end, I cured my fear of flying by going to Australia – because, if you can be scared for three hours on a short flight, you simply cannot keep up the fear for 18 hours on a long flight. In the end, the body just gives up and relaxes.

-Azerbaijani soldier guiding you: “You come here and show sympathy but we know you will go away and write something different”. Did that soldier tell the truth? What would you like to say him today?

-I understand him. He expressed his feelings honestly. I hope I did not let him down.

-Would you like to come back again to Azerbaijan, Khojaly, Agdam? Have you ever been in Baku?

-I only passed through Baku on the way to Agdam. I know Baku is a beautiful city. I would be interested to visit Azerbaijan, if the opportunity arose and the circumstances were right.

Hafiz Ahmadov

Comments

Show comments Hide comments